ICA’s ‘Dance/Draw’ exhibition worthy of second look. And a third and a fourth.

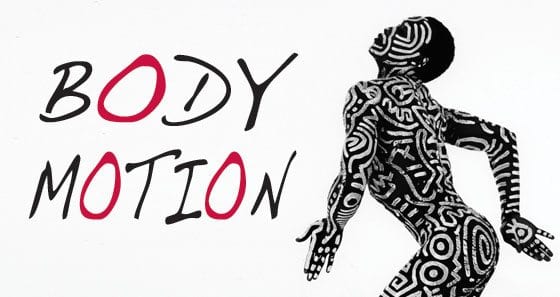

Tseng Kwong Chi Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring, 1983, Silver gelatin selenium-toned print Muna Tseng Dance Projects/Estate of Tseng Kwong Chi and courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, photograph by Tseng Kwong Chi ©1983 Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc. New York Body drawing by Keith Haring © 1983 Estate of Keith Haring, New York.

Tseng Kwong Chi Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring, 1983, Silver gelatin selenium-toned print Muna Tseng Dance Projects/Estate of Tseng Kwong Chi and courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, photograph by Tseng Kwong Chi ©1983 Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc. New York Body drawing by Keith Haring © 1983 Estate of Keith Haring, New York.

ICA’s ‘Dance/Draw’ exhibition worthy of second look. And a third and a fourth.

| Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.065), early 1960s Crocheted copper and brass wire 94 x 17 (diameter) inches, Anonymous Collection. Photo: Laurence Cuneo. |

“Dance/Draw,” the fascinating exhibition on view through Jan. 16, 2012 at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA), threads an illuminating path through the complex cacophony of art over the past five decades.

The exhibition traces the journey of the line and the connections between visual art and dance since the 1960s through sculpture, dance, photography, video, drawings and performances. In the assembled works, drawing emerges as a sort of performance. And dance becomes a kind of drawing, etching arcs and lines in space.

Coinciding with the 75th anniversary of the museum, “Dance/Draw” is the first exhibition organized by ICA Chief Curator Helen Molesworth. She brings together works by some 50 dancers and visual artists, and with her curatorial colleagues introduces each with an essay in the exhibition’s elegant catalog.

One of Molesworth’s muses is choreographer and dancer Trisha Brown, who in the ’60s began exploring the affinities and blurring the boundaries between visual arts and dance. The subject of a 2002 exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art, “Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue 1961-2001,” Brown is here represented in videos, photographs, a live dance installation and her own drawings. On Nov. 11-13, the ICA will host performances by the Trisha Brown Company, which she founded 41 years ago.

In the first gallery, a section entitled “More Than Just the Hand” presents works that are not hand-drawn illustrations, but instead, multimedia renderings of moments as well as lines and textures.

Trisha Brown dipped her toes in charcoal to draw the calligraphic “Untitled” (2007), an image that is both a record of an event and a work of art.

In William Anastasi’s ink and graphite drawings, wobbly lines nest like metal filings drawn to a magnet. He composed them in a sort of performance, with his eyes shut, as he rode the subway en route to his weekly chess games with revolutionary dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, who made chance and change subjects of dance.

David Hammons repeatedly bounced a basketball coated with “Harlem earth” to fashion “Basketball Drawing” (2001). Lebanese artist Mona Hatoum composed her quartet of “Hair Drawings” by arranging black strands on handmade ivory paper. In his wry “Snail Drawings,” Daniel Ranelli photographed a group of snails he placed in the sand in tidy formations and then showed them fanned out in their own constellations.

Crafted by pioneering composer and musician John Cage, Cunningham’s partner in art and life, is a pair of handmade papers made of herbs and flowers entitled “Wild Edible Drawings”(1990). Bahamian Janine Antoni used her mascara-laden eyelashes to create the delicate lines that fill her drawing “Butterfly Kisses” (1996-99).

The section entitled “The Line in Space” presents works that extend the line beyond the frame. These three-dimensional structures invite interaction, provoking the viewer to examine them from different angles. Artful lighting casts shadows through the nested basketry of Ruth Asawa, vertical spirals of crocheted metallic wire. Fred Sandback’s sculptural study suspends three strands of acrylic yarn from the ceiling to the floor. Evoking the strings of a musical instrument, the blue, red and yellow yarns and their shadows seem to carve the air into columns and panes.

As mid-century minimalists focused on the fundamentals, the grid emerged from its behind-the-scenes status as a compositional tool. Brown adopts the grid in the gallery-sized installation, “Floor of the Forest” (1970). Like a giant net, its sloping ropes hold assorted used clothing and, at predetermined times (Thursday evenings and weekend afternoons) also dangle a pair of her dancers, who silently crawl among the ropes and poke through the jackets and sweaters as if they are cocoons.

As Brown and her contemporaries playfully and often with great beauty investigated the building blocks of their art form, they moved dance off the stage onto plazas, the sides of buildings, roofs and mountaintops. The section entitled “Dancing” renders their pioneering experiments through photographs, films and drawings.

A wall-sized video projection shows an iconic performance by Yvonne Rainer, along with Brown a founding member of the seminal Greenwich Village Judson Dance Theater. Wearing a black top and pants, she dances her mesmerizing “Trio A” (1978). Debuted in the ’60s, her flowing, narrative-free study of pure movement launched a thousand classes in modern dance.

In another large video, choreographer William Forsysthe conducts a droll demonstration of his craft in the soberly named “Lectures from Improvisation Technologies” (2011). As he maneuvers his body to show each element in a dance composition, animated lines track his movements, making visible the implicit 3-D geometry of dance.

Born in Ghana and now living in London and New York, Senam Okudzeto combines comedy, art history and social commentary in her video and installation, “The Dialectic of Jubilation; Afro Funk Lessons” (2002-05). Partly a tribute to African American artist Adrian Piper, who instructed a white audience in her video “Funk Lessons” (1983), Okudzeto shows herself teaching a group of Europeans how to dance to the Afrobeat music of Nigerian Fela Kuti.

In “The Breaks” (2000), a 5×5 grid of freeze-frame photographs, Mexican artist Juan Capistran break-dances in an art gallery on a square of lead — a floor sculpture by the archetypal minimalist Carl Andre.

The fourth section, “Drawing,” looks at the metamorphosis of figure drawing through media as varied as 3-D digital imaging, neon and body paint.

With a nod to tradition, the works include Fiona Banner’s painstakingly hand-drawn covers of books designed to teach amateurs the essentials of life drawing. Nearby, another affectionate and humorous installation introduces the Friends of the Fine Arts (FFARTS). The artists’ collective gathers periodically for a “life drawing circle” that brings a contemporary skill-sharing ethos to the Beaux Arts practice of drawing nude models. Members don the poses and props of a particular period — say Old Testament stories — and swap roles as curators and models.

Dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones is the subject of two works. In photographs by Tseng Kwong Chi, he poses covered head to toe with white geometric patterns that artist Keith Haring has painted on his body. A mesmerizing 3-D projection by the OpenEnded Group, “After Ghostcatching” (1999), shows Jones in shimmering afterimages. As he dances, his figure dissolves into meandering ribbons of color.

The exhibition will reward repeated visits. Among the works that will draw you back is Sadie Benning’s 29-minute animation, “Play Pause” (2006). Her gouache drawings spin across two screens to Solveig Nelson’s pulsing sound track. Benning’s raw and tender cartoons take the viewer on a stroll through a teeming city, from its discos and soccer games to parks and storefronts. Her video is an urban rhapsody in the tradition of “Manhatta,” a 1920 silent film by photographers Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler. Their visual paean to the energy and grandeur of a young Manhattan has a worthy successor in “Play Pause.” With hints of post-9/11 tension (an occasional surveillance-camera view), Benning’s animation celebrates the persistent variety and verve of city life.

And with variety and verve, Molesworth’s exhibition honors generations of artists whose ephemeral subject is the human body in motion.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)