When it comes to being a doctor, cultural competence is just as important as physiology, says Dr. Augustus A. White III. According to the Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Medical Education at Harvard University, cultural understanding is key to equitable health care in the United States.

“Just as doctors need to know how to take a history and do a physical exam in order to provide good care, they should also have a basic sense of their patients’ social and cultural circumstances,” he writes. “Unequal care thrives on differences between doctors and their patients, on poor communication, on stereotyping, on misconnections in the relationship between the two.”

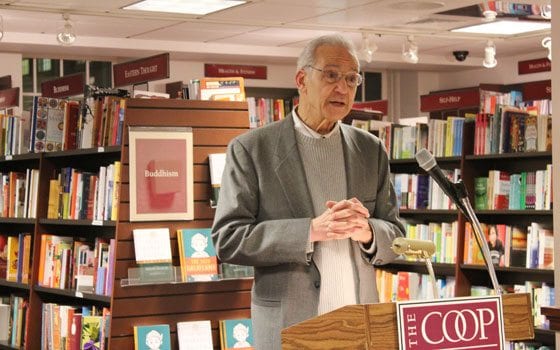

The 74-year-old was the head of the Culturally Competent Care Education Program at Harvard University, which aims to incorporate cultural awareness into medical education.

But the path to becoming one of the greatest champions for health care equity was not always easy. In a new memoir, “Seeing Patients: Unconscious Bias in Health Care,” released just weeks ago, White recounts his struggles and successes breaking down racial and cultural barriers in the medical field.

White grew up in Jim Crow-era Memphis, Tenn., where separate hospitals, separate schools and separate movie theaters marked his childhood. But his loving and proud family taught him never to feel inferior to anyone. Determined to be a doctor like his father, White excelled in academics and athletics, and at the age of 13, moved to Massachusetts to attend Mt. Hermon School for Boys.

He eventually matriculated into Brown University at a time when the school only accepted four or five black students a year, and after graduation, entered Stanford Medical School as its first African American student. White then completed his surgical training at Yale, where he was the school’s first African American resident.

The new surgeon then enlisted as a combat doctor to serve in the Vietnam War. White treated American soldiers whose limbs had been torn apart in explosions, and on his own time, traveled to a leper colony to treat Vietnamese patients whose hands and feet had lost functionality from the disease. Moving between the two operating rooms, White saw “man’s inhumanity to man and nature’s cruelty to man — both of them an absolute bitch.”

But in Vietnam, White also saw the common humanity that bound people of different races together. “Once you make that incision, once you look inside, everybody is the same,” he writes. “Open up that skin and underneath it’s all one. The reality of the body tells this to you.”

After a year in Vietnam, White packed his bags again, headed to the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, where he earned a Ph.D. for his research on the biomechanics of the spine.

After these two years abroad, White returned to Yale, but this time as a newly minted faculty member. In this position, he served on the admissions committee for Yale’s medical school and residency programs, with the aim to bring “more black students into what was an almost completely lily-white environment.”

“My main idea,” he writes, “was to wake Yale up to the fact that there were excellent, deserving, qualified African Americans who, for a variety of reasons, were more or less invisible to the admissions process. I wanted those young people to have a chance rather than no chance.”

White also focused on the unequal health care blacks were receiving in the United States. As he details in his book, blacks receive fewer kidney and liver transplants and less pain medication for the same ailments than whites do. Blacks are also more likely to have amputations and open surgical procedures than less risky laparoscopic ones.

But unlike most, White’s global worldview allowed him to see that blacks were not the only minority group suffering from disparate health care. In addition, women, Hispanics, Asians, the poor, the elderly, non-English speakers, gays and lesbians and obese people suffer from unequal medical treatment.

For White, these disparities are rarely the work of deliberate racism, but instead are the result of unconscious bias and a lack of cultural training in the medical field. So he set out to change this, pushing for cultural competence curricula in medical education.

But in White’s view, patients also bear responsibility for their medical treatment. In his book, White outlines tips for patients to optimize a visit to the doctor’s office.

“Humanize your doctor,” he writes, “meet your doctor half-way… Read about your symptoms or disease, if you know it,” he also advises, and “do a ‘teach back’ with your doctor.”

In a “teach back,” the patient repeats any instructions or explanations the doctor gave to confirm his or her understanding. White also suggests, “take a friend or relative into the doctor’s office with you if you feel you need to.”

After rising through the academic ranks at Yale, where he became the first African American professor of surgery, White moved to Harvard, where he was made the first African American department chief at any of the university’s teaching hospitals. Eventually, White formed the Culturally Competent Care Committee, which he continues to run.

Although White has made important strides to diversify the medical field, he still sees a lot of work to be done. In courses at Harvard Medical School, “there is attention paid to cultural bias and cultural competency,” he explained to the Banner. “But it doesn’t have the financial or institutional [support] that in my opinion, I think is needed.”

“I see continued progress,” he explained. “I think it’s going to be slow, but the issue isn’t going to go away. Cross-cultural communications is something we all need, whether we’re doctors or not.”