Black centers, quarterbacks and coaches were not always the norm in professional football.

While the New England Patriots and other charter members of the American Football League celebrate their 50th anniversary this year, and the National Football League (NFL) was founded in 1920, the Washington Redskins fielded an all-white team until 1962. With rare exceptions, the positions of quarterback, middle linebacker, center and strong safety were considered too cerebral for black athletes, though some had, of course, played those very positions with distinction in college or the Canadian Football League.

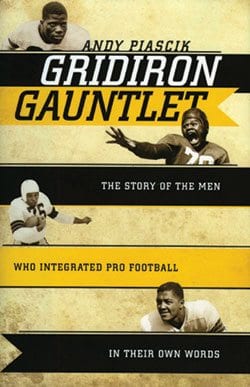

Author Andy Piascik’s new book, “Gridiron Gauntlet: The Story of the Men Who Integrated Pro Football, in Their Own Words” (Taylor Trade Publishing, 246 pages), is a valuable oral history of the players who broke down the racial barriers of the NFL and the old All-America Football Conference (AAFC) in the 1940s and 1950s. It features the vivid recollections of such celebrated stars as Hall of Famer Joe “The Jet” Perry and AAFC trailblazer John Brown, and lesser-known bruisers like Harold Bradley of the mid-1950s Cleveland Browns and Charley Powell of the early 1950s San Francisco 49ers.

The 12 players interviewed in “Gridiron Gauntlet” recount their youth and scholastic sports careers. Many were products of the Great Migration from the South to industrial centers such as Gary, Ind. (such as Brown and early Baltimore Colts quarterback George Taliaferro), and Chicago (like Sherman Howard of the New York football Yankees). Contemporaries of baseball’s Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby, these men paved the way for players like Ollie Matson, Jim Brown and Jim Parker, whose busts now line the corridors of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

A few themes recur throughout the chapters. Several of the former players said they looked up to UCLA standouts Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, who signed with the Los Angeles Rams in the mid-1940s. To a man, the interviewees express admiration for Cleveland coach Paul Brown, who employed stars like Marion Motley, Bill Willis and Len Ford — and even a black punter, Horace Gillom — as early as the 1940s.

They speak of teammates who should not have been cut or waived, black players not used properly by their coaches, and mid-1950s Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers running back Henry Ford, who some believe may have been blacklisted from the NFL because he was married to a Syrian woman. Former players John Brown and Bradley even said they feel that segregation had some merits — the pro football players got to know the prominent black musicians of their day because they all stayed in black-owned hotels.

In a collision sport like football, one might expect to hear stories about racial slurs uttered after violent or dirty plays. Experiences of that nature vary, though; most men say epithets were few and far between, given the number of white players from segregated Southern and Southwestern backgrounds in pro football in their day.

Both Brown and Taliaferro tell the story of a Texan teammate who felt he was giving the blacks on the ballclub a compliment when he said, “You know what, you n*****s can really play ball!” Silent looks of discomfort, both at the offender and between the black players, prompted an apology rooted in regional habit. Later, Brown and the Texan became fast friends.

“Gridiron Gauntlet” is a worthy addition to the scholarship on race in American sport. Because every word comes from the participants, the work, while serious, has the informality of a living room conversation with an accomplished and gregarious family member. Massachusetts readers should note the inclusion of mid-1950’s Chicago Bears and Chicago Cardinals halfback Bobby Watkins, who hails from New Bedford. He was recruited by the University of Massachusetts, Brandeis University and the University of Connecticut, but those schools didn’t have the kind of major college football program he felt he belonged in — ultimately, he chose to attend Ohio State.

Though race remains an issue in the coverage and fanfare surrounding pro football, “Gridiron Gauntlet” sheds light and perspective on a time when Sunday’s heroes were high-topped and crew-cut products of a largely Jim Crow society. Not long after Robinson made the grade in Major League Baseball, ballplayers who’d previously had little or no experience with interracial socialization began competing for the same positions and smashing each other in practices and games. Because these black and white warriors learned to get along in those all-important days, generations of fans have been the beneficiaries of the intelligence, power and speed of a more level playing field.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)